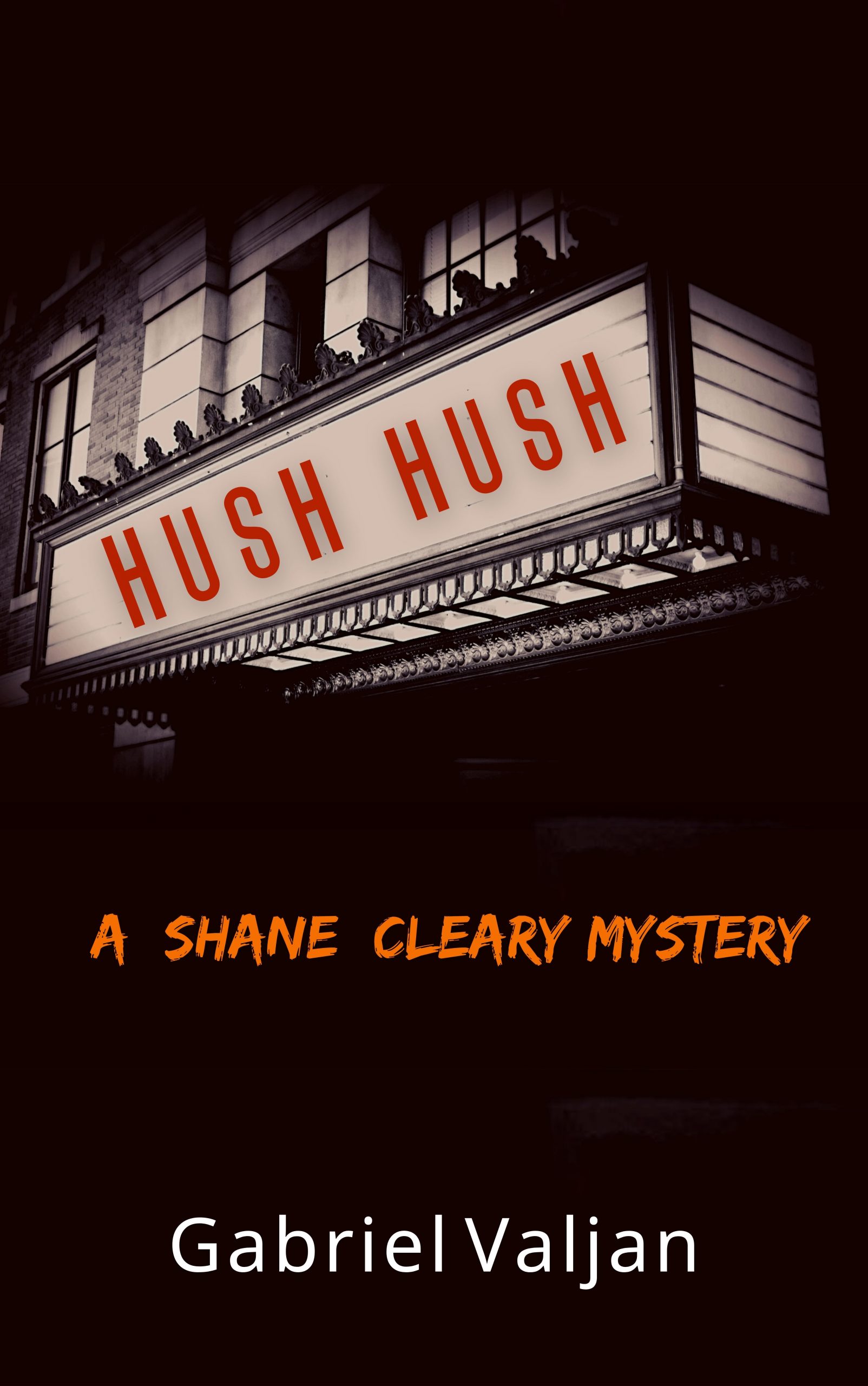

Shane Cleary is living a comfortable life. He has money. He has a girl.

But a visit from a friend shakes up his status quo. Chess may be the metaphor, but the case is one that lifts the lid on problems nobody in Boston wants to talk about.

Murder. Race. Class. It’s all Hush Hush.

Neither the crime nor the verdict is simple, and yet it is Black and White.

Shane will need more than a suit of armor if he wants to play knight. Can Justice be found? And at what cost?

He’s a retired PI. At least that’s what he told himself and his girlfriend Bonnie. He even let his license lapse. But the lure is still there when an old friend gets him involved with someone who needs his expertise.

He decided he could help out by doing “research” instead of investigating. It turns out to be a very hot case. More than one person wants to do him bodily harm.

His research leads him to people who want him and his research to disappear. Bonnie’s not crazy about all of it either. How is he going to reconcile all this? You need to get involved and read this book to find out. You might also want to pick up the first two Shane Cleary books, Dirty Old Town and Symphony Road.

I’m ready for the next one. I hope Mr. Valnan is a fast writer.

I pulled the door open to Charlie’s Sandwich Shoppe. The spelling might’ve been from Middle English and seemed as medieval as Robin Hood, but a Greek owned the place. On any given day, Arthur the proprietor was Art or Artie and, like his old man before him, he worked the grill. Charlie’s was open twenty-four a day, seven days a week, including all the major holidays, Jewish or Gentile.

I’ve eaten breakfast countless times at his counter. The place did have tables, but it was designed for food on the move, men on the job, and people on the make. Walk into the shop and it was sometimes cops on one side of the room, gangsters on the other. Peace was a meal until everyone returned to the pavement outside, and there was no one-way streets about it: the South End was trouble. Charlie’s eggs, hash, bacon, and stiff coffee worked harder than the UN.

Charlie’s dated back to the Twenties. Framed photographs, some of them signed and some not, hung on the wall and told a history most Americans had forgotten, and why I supported the place. The Negro Motorist Green Book in hand told jazzmen and other itinerant talent that Charlie’s was a safe haven. In all of Boston, this was the one place where they could eat and, for a time, one of the few places where they were allowed to eat. Segregation ruled Boston until 1973, when public housing and schools were desegregated.

Sammy Davis, Jr. hoofed outside Charlie’s door for change, and he performed with his family at The Gaiety Theatre, which is now in the Combat Zone. Barred from the vaudeville stages in town, black talent played the burlesque houses. Audiences in these naughty houses were integrated. Some of the acts were women-owned and they managed acts that toured the TOBA circuit. TOBA stood for Tough on Black Asses.

There were no police officers in the place when I sat next to a familiar face at the counter. People called him Charcoal. He was thin as a stick and dark as his nickname. We sat on stools covered in cracked vinyl, and opposite wooden refrigerators there since Charlie’s opened its doors in 1927. Eggs sizzled, bacon puckered and sputtered, and conversations tumbled in and out like the tide. Arthur could hear above the din and asked me what I wanted, and I told him. “Turkey hash.”

A waitress placed a cup and saucer before me and poured caffeine. Charlie’s coffee was unleaded, and dark as unchanged oil and stiffer than Niagara starch. While I waited, I sipped and stared out the window. Life on Columbus Ave was a steady traffic of folks to and from the trains at Back Bay station around the corner.

There was another slice of history. Back Bay was the epicenter of the Pullman Porter Strike, conducted and carried to victory by the first black union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. Their office was above Charlie’s Shoppe. Membership was comprised of black men from the south. They traveled throughout the homeland for the union’s cause for better wages and working conditions. I doubt they slept a wink on the train through Jim Crow territory.

I was two forkfuls into my turkey hash, and Charcoal was on his third cup of joe when a burgundy Cadillac, with all the trimmings, rolled up to the front of Charlie’s. The man driving it wore large sunglasses and passed for a thinner version of Isaac Hayes. He wore business threads, and his head was shaved and glistened like a chocolate bullet. He had his back to the car and was facing us when a car stopped parallel to his parked car. Boston Police.

Arthur stopped and worked a washcloth over his hands. Every head was turned to the spectacle. Our Isaac Hayes heard a cop call him out. There was glass between us and him, but it wasn’t hard to guess the conversation on the street. Patrons of Charlie’s had seen this Movie of the Week and they knew the script. The question was whether Isaac stuck to his lines or improvised. The cop was almost out of the car, his head visible over the roof of the patrol car. He yelled, “Hey, Boy.”

Isaac hadn’t heard him until he’d seen the reflection of the officer and the cruiser in Charlie’s window. He stopped, removed his glasses, and turned around. A customer leaving Charlie’s propped the door so we could eavesdrop.

“Hands where I can see them.”

“Is there a problem, Officer?”

“We ask the questions, not you.”

Isaac stood his ground. The cop, out of the vehicle now, walked around the back of his car. His partner exited the passenger side. I expected a citation for being double-parked.

The cop jabbed his finger. “What are you doing?”

There was distance between the officers and the young man, but they were closing in fast. I understood what they were doing. They were asserting dominance and they wanted to spark a reaction. With enough space between them, if Isaac ran, one of the policemen could sprint and catch him from an angle. They’d talk smack as they approached, looking for an excuse to cuff him. If Isaac answered wrong, used the wrong tone of voice, they would ride him.

“I asked you what you’re doing.”

Isaac was smart. He raised his hands. Now came the dilemma because nothing he said mattered.

“Did I tell you to put your hands up?”

“No.”

“You going to answer me?” The tone of voice was sharp as a knife’s edge. “I asked you what you’re doing here.”

“Here to pick up a sandwich before work, Officer.” He glanced over his shoulder.

I hear courtesy and respect in the answer. Cops heard sarcasm.

“A sandwich, is that right?”

“Yes. A sandwich before work.”

“You have a job?”

Another lure, an insult disguised as a question. When cops testified in court, they’d tell the jury that they repeated answers as a way to verify information, but nobody asked them how they asked their questions.

The partner walked around the Cadillac. He used his foot to test the fender. He aimed to test a man’s pride in his set of wheels. His hand touched the rear light and he ran his hand over the body as if he checked for dirt. “This your car?”

“Yes.”

The cop closest to Isaac said, “You sure about that?” He glanced over his shoulder. “We run those tags and we won’t hear it was stolen.”

“No.”

“No what? What are you trying to say? I don’t understand you when you mumble.”

Another classic strategy. Isaac spoke clear as sunlight and kept his answers trimmed to simple. The more you talked, the more your own words were used against you. If he denied mumbling, he’d look defensive, and the cops would consider Isaac as dangerous as the third rail.

I waited for them to ask Isaac what his job was and where. They’d look at the Cadillac while he talked. Their looking at the car implied they didn’t believe the job matched the income to purchase a luxury vehicle, or that a Cadillac was a pimpmobile. The two cops might then tag-team Isaac with questions. Cops counted on confusion and if Isaac so much as stuttered, they would accuse him of being drunk, drugged, or agitated.

Isaac answered, “The car is mine. Registration is in the glove compartment.”

“License?”

“On me, but you can reach into my breast pocket for it.”

“On you?” the lead cop said. The smirk showed teeth.

“In my wallet, where I keep my cash so I can pay for my sandwich.”

The partner chimed in. “Glove compartment include proof of insurance?”

“Registration and insurance are in the glove compartment, yes.”

Now the lead cop was less than a foot away from Isaac. “Now, let me understand you right. You’re giving us permission to search your car?”

“Registration and insurance are in the glove compartment.”

“That’s not what I asked you, son.” The officer was eye-to-eye with Isaac. Any closer and it was a date. He turned and pointed to the car. “We won’t find anything else inside?”

Charcoal next to me said. “I think young blood could use some help from the community, right about now.” He got off the stool and walked to the open door. Other men followed him and formed a line in front of Charlie’s Sandwich Shoppe. I joined them.

The cops’ disposition changed immediately when he counted us.

“You folks go on back inside. This doesn’t concern you.”

A long hard minute passed and not a word was said. There was nothing but hard, tired stares. Isaac had not put his hands down and he hadn’t moved from where he was standing. Arthur appeared, a brown bag in his hand. He handed it to Isaac. “Breakfast is on me, and I hope the experience doesn’t stop you from visiting Charlie’s again.”

“This is a police matter,” the cop said to Arthur.

“And this is my business, and this young man is a customer.”

The cop moved in on Arthur. “This does not concern you.”

Charcoal stepped forward. “I suggest you officers either search the car, or call it a day.”

“You suggest?”

“Indeed, I do—and I advise you to heed my advice.”

The cop approached. When he did, the men behind Charcoal took one step forward and held the line. The cop stared into Charcoal’s face. “Heed your advice, and who the fuck are you?”

Charcoal flinched a smile. “I’m an attorney, labor and civil rights among other things, and I’d be happy to provide you with my card.”

“You’re a lawyer?”

“What’s the matter, Officer? You’ve never met a Negro lawyer or thought a black man might have more education than you and your forebears combined.”

“You know nothing about my forebears.”

“Oh, but I do, son. I do.”

The senior cop reassessed the situation. He looked at each man behind Charcoal, including me. Cops did this to save face. The pair backpedaled and got into their car. Arthur stood next to the opened door and thanked each of his patrons as they entered his shop. Charcoal and I were the last in the long line. I asked Arthur if I could make change for a phone call.

Arthur said I could use the house phone and pointed me to where I could find it. I called John and he answered. I said I’d be down to his place to talk with his friend, the kid’s father. “You’ll take the case?”

“I didn’t say that. I want to talk the man first, and John?” He waited. “What was with the chess metaphor and all?”

“I wasn’t about to talk street, in front of your lady.”

“You showed up unannounced. How did you find me?”

John said Bill’s name and, “Did something change your mind?”

“Change, no. More like I saw something that made me reconsider.”

“Watched something on television?”

“That’s make-believe. I’m talking about real life.”

***

Excerpt from HUSH HUSH by Gabriel Valjan. Copyright 2022 by Gabriel Valjan. Reproduced with permission from Gabriel Valjan. All rights reserved.

Gabriel Valjan is the author of the Roma Series, The Company Files, and the Shane Cleary Mysteries. He has been nominated for the Agatha, Anthony, Silver Falchion Awards, and received the 2021 Macavity Award for Best Short Story. Gabriel is a member of the Historical Novel Society, ITW, MWA, and Sisters in Crime. He lives in Boston.