Murder is Not a Girl’s Best Friend

March 18th, 2022Murder is Not a Girl’s Best Friend

by Rob Bates

February 28 – March 11, 2022 Virtual Book Tour

Synopsis:

Journalist-turned-amateur-sleuth Mimi Rosen is back with her father Max for another action-packed tale of murder and intrigue in New York City’s Diamond District.

A Reverend from Africa has found a sparkling $20 million diamond that he hopes will free his continent from the scourge of blood diamonds. But this attempt to do good soon turns very bad. After the diamond is stolen and leads to a series of murders, Mimi discovers both the diamond and the Reverend have a less-than-sparkling history.

Soon, Mimi is investigating a web of secrets involving a shady billionaire, a corrupt politician, Africa’s diamond fields, offshore companies, as well as an activist, filmmaker, computer genius, and police detective who may or may not be as noble as they appear. Is the prized gem actually a blood diamond?

Book Details:

Genre: Mystery

Published by: Camel Press

Publication Date: February 8th 2022

Number of Pages: 218

ISBN: 1942078188 (ISBN13: 9781942078180)

Series: Diamond District, #2 || Each is a Stand-Alone Mystery

Purchase Links: Amazon | Barnes & Noble | Goodreads

ISLAND BREEZES

They say diamonds are a girl’s best friend. Maybe yes. Maybe no. One thing is for sure. Murder is not a girl’s best friend.

Once again Mimi is putting herself in danger. Doesn’t she ever learn? She keeps telling herself and others that she won’t do any investigating. Ha! She just can’t leave it alone.

There are many twists and turns in this book. So many that you’ll probably not figure out who the bad guys are. There just appear to be so many of them.

Thank you, Mr. Bates, for another trip through the Diamond District and through the eyes of Mimi Rosen. I enjoy the way she just keeps on muddling through and look forward to her next adventure.

***Book provided by PICT without charge.***

Read an excerpt:

CHAPTER ONE

Mimi Rosen felt terrible. She felt like crap. She was overcome by guilt—the kind that gets lodged in your throat and stays there. Her day at the “Social Responsibility and the Diamond Industry” conference had been draining and dispiriting, as one speaker after another grimly recited the industry’s ills. They acknowledged that conflict diamonds—which fueled civil wars in countries like the African Democratic Republic, or the ADR—were far less of a problem, and many diamond mines benefited local economies.

Then came the “but.” As Mimi’s father said, “in life, there’s always a but.”

“Beautiful gems shouldn’t have ugly histories,” thundered Brandon Walters, a human rights activist known for his scorching exposés of the ADR’s diamond industry. “This—” he aimed his finger at the screen behind him, “is how ten percent of the world’s diamonds are found.”

Up popped a photo of an African boy, who couldn’t have been older than sixteen. He was standing in a river the color of rust, wearing nothing but cut-off jeans, bending over with a strainer. Mimi could see his vertebrae under his skin, feel the sun beating down on him, sense the stress and strain on his back.

“That kid is paid two dollars a day for his labor,” Walters declared. “If you sell diamonds, this may not be your fault.” He paused for emphasis. “But it is your responsibility.”

Walters had sandy-blonde hair, high cheekbones, a perfectly trimmed goatee, a ponytail that flopped as he talked, and a South African accent was so plummy it sounded affected. He looked to be in his mid-twenties but had the bearing and confidence of someone ten years older. Unlike the other activists, who delivered their speeches in whispery monotones with their eyes glued to the podium, Walters planted his feet firmly at the center of the stage and stood on it like he owned it. He peppered his talk with splashes of theater, dropping his voice to signal despair, or cranking it up to roar disapproval.

Mimi didn’t want to close her eyes to his message, but knew she might have to, to preserve her sanity. Diamonds were now how she made her living. She had been working at her father’s company for over a year—a fact she sometimes found hard to believe. She occasionally dreamed of again working as a reporter—the only thing in life she had ever wanted to be. But journalism had become an industry that people escaped from, rather than to.

She had hoped the conference would inspire her. She had even convinced her father, Max, to come. Instead, the sessions made her feel depressed and sorry for herself—which didn’t feel right, as she was hearing about extreme poverty in a plush New York City auditorium with the air conditioning cranked, while the summer sun broiled the streets outside.

She also knew the industry’s problems weren’t so easy to fix. When Mimi started working at her dad’s company, Max seemed intrigued by her idea of a socially-responsible diamond brand. She was excited to help change the industry.

Then the project ran into roadblocks. She never quite determined what a “good” diamond was. What if it was unearthed by one of the diggers Brandon Walters talked about, who earned two dollars a day? Human rights activists condemned that as exploitive. Yet, they also admitted those workers had few other sources of income and would be far worse off if the industry vanished. They didn’t want to kill the business; they wanted to reform it. Mimi wasn’t an expert on any of this—and even those who were didn’t always agree.

Mimi spent many nights and weekends researching these issues, and ended up frustrated, as the answers she sought just weren’t there.

When her project began losing money, her father started losing patience. Mimi hoped that dragging her father to this conference would reignite his interest. Nope.

“These people act like everything is our fault. All minerals have issues.” Like many in the diamond business, Max believed his industry was unfairly picked on. He fixed his yarmulke on his bald head, so it stayed bobby pinned to one of his side-tufts of hair. “I haven’t done anything wrong. I’m only trying to pay my rent.”

Max spent most of the conference with his arms crossed, his face toggling between bored and annoyed. If he had a phone, he’d probably spend the day staring at it. But he didn’t, which was another issue.

Following Walters’ talk, he leaned over to Mimi. “I should call Channah for my messages.”

Mimi gave him her mobile and a dirty look. He had already borrowed her phone six times that day. She considered lecturing her father to get over his stupid aversion to buying a cell phone, so he didn’t constantly pester the receptionist to see who called. But she’d also done that six times that day.

Besides, she was intrigued by the day’s final speaker.

Abraham Boasberg grabbed the crowd’s attention the moment he stepped on stage. “I believe there is a reason that God put diamonds in the poor countries and made rich countries desire them,” he bellowed, puffing out his barrel chest. “And I’m going to prove it.”

Mimi sat up and thought, who was this guy?

She soon found out. Boasberg was six feet tall, stocky, bearded, with a bright red yarmulke capping a salt-and-pepper mop of curly hair. He worked in the diamond business, and his words came fast and forceful. Like Brandon Walters, he seemed to savor being the center of attention. He had a mike clipped to his suit and prowled the stage like a panther. His presence filled the auditorium.

“This whole conference, we have heard about the problems of our trade. They are real. The people who dig diamonds are part of our industry. They deserve to be treated fairly.

“But we must do more than just complain,” he declared, holding up his index finger. “We need solutions!

“What if diamonds, which once helped rip the African Democratic Republic apart, could put it back together? What if they built new roads, schools, and hospitals?” He stopped and took a breath, his chest heaving. “What if diamonds became symbols of hope?”

Max returned to his seat and handed Mimi back her phone. She was so entranced with Boasberg, she barely noticed.

“A few months ago,” Boasberg proclaimed, “a local Reverend in the African Democratic Republic found a one-hundred-and-seventeen-carat piece of rough on his property. It has since been cut into a sixty- six-carat piece of polished, about the size of a marble. It has been graded D Flawless, the highest grade a diamond can get. It’s the most valuable diamond ever found in the ADR. It’s worth twenty million. Easy.”

A giant triangular gem appeared on the screen behind him, gleaming like a sparkly pyramid.

Max’s eyebrows shot up. This guy was talking diamond talk, a language he understood.

“But that is more than a beautiful diamond.” Boasberg declared, sweat beading on his forehead. “That is the future.”

“Here’s what usually happens with diamonds in the ADR. In most cases, miners hand them over to their supporter, who’s basically their boss who pays their bupkis. Or, if they’re freelance, they’ll sell them to a local dealer, who pays them far below market value. The miners don’t know how much the diamonds are worth, and they’re usually hungry and just want a quick buck.

“And since the ADR has no money to police its borders, most dealers smuggle diamonds out of the country to avoid taxes. As a result, the ADR gains little from what comes out of its soil. Its resources are being systematically looted.

“When I met Reverend Kamora, I told him, consumers are turning away from diamonds because they believe they don’t help countries like yours. That further hurts your people. Now, instead of working for two dollars a day, they’ll do the same work for even less.

“But what if we can flip the script? What if this diamond helps your country? And what if we let people know that? That will increase its value. It’s documented that people will pay extra for products that do good, like Fair Trade Coffee. It’s the same reason kosher food is more expensive. It’s held to a higher standard.

“If we get more money for this diamond, soon every gem from the ADR will be sold this way. We’ll do an end run around the dealers who have robbed the country blind. We’ll turn ADR diamonds into a force for good.” He pivoted to the screen. “Let’s talk about this gorgeous gemstone.

We wanted to call it the Hope Diamond. That name was taken.” A few members of the audience tittered.

“We’re calling it the Hope for Humanity Diamond. Four weeks from now, we’ll auction it from my office, live on the Internet. We want the whole world to watch. We’ll even sell it in a beautiful box produced with locally mined gold.” On screen, a glittering yellow box appeared. The diamond sat inside it, perched like a king on a throne.

“What celebrity wouldn’t want to wear a diamond called the Hope for Humanity?” Boasberg asked. “It will make them look glamorous and morally superior.”

The audience laughed.

“This diamond—” he exclaimed as spit flew out of his mouth, “will transform a continent.” He stretched out his arms, revealing pit stains the size of pancakes.

“So many conferences talk about Africa, but you never hear from people who actually live there. And so, I’ve flown in the Reverend who found the diamond, to talk about what it can do for his country. Reverend Kamora, can you come here, please?”

The auditorium grew quiet as small middle-aged Reverend Kamora shuffled to the front. He walked slowly, gripping the guardrail as he climbed the stairs to the stage. When he finally arrived at the microphone, Mimi could barely hear him; his voice was low and delicate, with the soft cadence of a bell.

“For years,” he began, “blood diamonds were a curse on my country. Things happened that were hard to describe. They haunt us still.” He paused, as he momentarily got choked up.

“The African Democratic Republic has known two decades of peace, but not one minute of prosperity. Like many people in my country, I dig for diamonds for extra money. It’s hard work. I don’t make much from it. But I have no choice.

“Many people who work in my country’s diamond fields don’t understand why people in the rich countries buy diamonds. Some believe they are magic. And when I found this gem in a riverbed, sparkling in the sun, I thought God had blessed me with a bit of magic.

“But God’s real gift came when I met Mr. Boasberg. He told me that we could hold an auction for this diamond, receive a better price for it, and ensure the proceeds benefit the people of my country.

“I hope you tune into the auction of the Hope for Humanity Diamond four weeks from today. Together, we can change my country’s diamonds from a curse to a blessing. That will really be magic.”

After a tough day, Mimi felt a smidgen of optimism. When Reverend Kamora finished speaking, her eyes were filled with tears. She peered at her father. He was asleep.

After Reverend Kamora toddled from the stage, Boasberg bounded back to answer questions.

A man approached the microphone in the middle of the audience. “Mr. Boasberg,” he asked, “what are you getting out of this?”

“Nothing,” Boasberg smiled. “I’m not even taking a commission. I see this as the way forward for the business that I love, and a country I care about.”

“Mr. Boasberg,” a second person asked, “how do we know the money will go where you say it will?”

“Our accounts will be posted online and completely transparent.

We’ll account for every penny.”

On it went, Boasberg swatting back every question with the grace of a tennis pro. Maybe it was the journalist in her, but Mimi was growing skeptical. Boasberg’s almost-Messianic tone struck her as too good to be true.

Just then, she heard a familiar voice at the microphone. It was Brandon Walters, the activist who spoke earlier.

“Mr. Boasberg, I’m intrigued by your new initiative,” he said. Mimi braced herself for the “but.”

“But when you talk about dealers who’ve robbed the country blind, you didn’t mention you were once partners with the worst offender.”

Boasberg’s nostrils flared. He looked down at Walters like he wanted to kill him.

The young activist plucked the mic from its stand and spun around to address the audience.

“For those unaware, Mr. Boasberg used to own a company with Morris Novak. During the civil war in the African Democratic Republic, Morris Novak was one of the biggest dealers in blood diamonds. He remains a significant player in the industry, though his main business today is money laundering. Diamonds are kind of a sideline.

“For years, I’ve sought to expose Morris Novak’s corruption. In response, he has repeatedly threatened to sue me. Our friend Mr. Boasberg could help by supplying information about Novak’s business dealings. He won’t.”

He circled back to Boasberg. “So, while it’s admirable you want to play a role in the ADR’s future, maybe first, you should come clean about your past.”

There was a smattering of applause.

Throughout Walters’ speech, Boasberg appeared ready to erupt, and when it ended, that’s what he did. “First of all,” he boomed, “you are correct, Morris Novak is my former partner. Let me emphasize former. I haven’t worked with him in six years. Is that long enough for you?

“Second, who the hell cares? This is old news. The problem with you non-government organizations, you NGOs, is you’re always pointing fingers. Maybe if you stop the holier-than-thou B.S., you could help do something good.”

Walters seemed to relish this reaction. “I’m just saying,” he shot back, “that given your history, and that of certain of your, shall we say, ‘associates,’ you’re an unlikely savior for the ADR.”

This sent Boasberg into a fury. The bickering grew so loud, even Max woke up.

The moderator—a middle-aged woman with silvering hair wrapped in a bun—hurried to the stage and declared question time was over.

“Thank you, Mr. Boasberg for that inspiring presentation,” she said, with a jittery squeak. “The conference organizers would like to present you this humanitarian award for your efforts.”

The award was likely pre-arranged and came off as awkward with Walters’ question hanging in the air. The moderator rushed through her praise of Boasberg, while he impatiently fingered the marble statue. When she finished, he stormed off the stage.

The moderator gamely tried to end the meeting on an upbeat note, saying it had many “impactful takeaways” and “urgent calls to action,” and reminding everyone to attend the post-conference cocktails in the next room. No one listened. They were digesting that final spectacle.

So was Mimi. Walters’ question had transformed Boasberg from a passionate plain speaker to another defensive diamond dealer, like her dad. Maybe he was too good to be true.

***

Excerpt from Murder is Not a Girl’s Best Friend by Rob Bates. Copyright 2022 by Rob Bates. Reproduced with permission from Rob Bates. All rights reserved.

Author Bio:

Rob Bates has written about the diamond industry for close to 30 years. He is currently the news director of JCK, the leading publication in the jewelry industry, which just celebrated its 150th anniversary. He has won 12 editorial awards, and been quoted as an industry authority in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and on National Public Radio. He is also a comedy writer and performer, whose work has appeared on Saturday Night Live’s Weekend Update segment, comedycentral.com, and Mcsweeneys He has also written for Time Out New York, New York Newsday, and Fastcompany.com. He lives in Manhattan with his wife and son.

Catch Up With Rob Bates:

RobBatesAuthor.com

Goodreads

BookBub – @robbates922

Instagram – @robbatesauthor

Twitter – @robbatesauthor

Facebook – @robbatesauthor

Tour Participants:

Visit these other great hosts on this tour for more great reviews!

Get More Great Reads at Partners In Crime Tours

Alphabet Love

March 16th, 2022Tell little ones just how much you love them with Alphabet Love—a heart-shaped board book that introduces children to the alphabet and celebrates everyday moments of love.

“C is for cuddle, wrapped up so tight. D is for dancing, twirling all night.” If you are looking for an alphabet book to give you the warm fuzzies, look no further. This sturdy board book highlights all the little moments that toddlers share with their loved ones throughout the day, from blowing bubbles, to exploring outside, to reading a book before bed. With cheerful, rhyming text and bright, playful illustrations, Alphabet Love makes it easy and fun to learn the ABCs.

ISLAND BREEZES

This sweet little board book is a good bedtime read. All the alphabet letters are illustrated by animals.

This book gave me the “warm fuzzies” and made me smile.

***Book provided without charge by Canaan of the Hatchette Book Group.***

Rachel Tawil Kenyon was born in Brooklyn, New York, and spent her teen years in Hollywood, California. Bringing her diverse experiences with her, she moved with her family to Nashville, Tennessee, where she writes, reads, and teaches. Rachel is known in her community for her enthusiasm working with young children and teenagers. She writes from the heart and encourages the kids she works with to do the same.

Anna Süßbauer grew up in Cologne, Germany, surrounded by art books, picture books, comics, and her father’s typewriter, on which she typed her own stories. Her decision to become a picture book illustrator was driven by a passion for graphic design and a love of clear structures and bright colors. Anna’s work is inspired by a whimsical sense of humor and her love for all kinds of animals, including her two dogs Eddie and Patsy.

Judgment

March 12th, 2022One Will Too Many

March 8th, 2022Synopsis:

A wealthy banker with a long list of secrets dies.

The bizarre crime scene stumps the local police…

… but a young doctor could be the key to solving the case.

Internist Julia Fairchild encounters banker Jay moments too late – the poor man is near death in his own dining room. At first no one can figure out what killed him, but the coroner soon confirms that it was homicide: Jay died of methanol poisoning, and now a murderer is on the loose. Julia knows how to catch a killer and she can cut through the noise like a scalpel through skin. She agrees to help the understaffed police force solve the case, but each clue only complicates her investigation further.

Can Julia dissect the deadly riddle and nail the perp, or will this be the first time a monster succeeds in giving her the slip?

If you love Louise Penny, Kelly Oliver, and PC James, you need this medical mystery! Find out why fans say, “I love the character Julia Fairchild!”

Don’t wait – Click the BUY button now!

Book Details:

Genre: Cozy Mystery

Published by: Finngirl, LLC

Publication Date: December 2021

Number of Pages: 206

ISBN: 978-1-7335675-7-2

Series: A Julia Fairchild Mystery, #4 || Each is a stand Alone Novel

Purchase Links: Amazon | Barnes & Noble | Goodreads

ISLAND BREEZES

Some might think only one will is one too many if that person has to die to leave it behind. If he left two wills behind, not only would that be one will too many but also a mess.

An even bigger mess could be the two who stand to inherit. One murder and any number of suspects.

It seems Julia Fairchild is once again in the middle of things. At least she has her deputy nephew to rely on. But still, her life could be in danger again.

It also causes problems with her latest boyfriend. Will he last any longer than the previous one?

I was sure I had figured out who the murderer was. I was wrong.

Thank you, Ms Peterson. I really do like Julia and hope you have another adventure for her coming up soon.

***A special thank you to PICT for providing without charge a copy of this book.***

Read an excerpt:

Julia arrived at the Hotel Montpelier just as Drake drove up. She took advantage of his simultaneous presence to make a proper entrance to the celebration in the Hotel’s Grand Ballroom. It had recently been refurbished to its original grandeur from the early 1920’s. She admired the beauty of the ceilings with their Art Deco design, recently uncovered by the removal of a false ceiling from a previous “upgrade.” The beautiful wood floor with exquisite inlaid mosaics shone from a recent floor polishing. The cherry and mahogany woodwork glistened in the light from the elegant crystal chandeliers which had also been hidden until now.

Julia and Drake were greeted by some of the other members of the restoration committee. Drake was the designated master of ceremonies while Julia’s primary duty was to personally welcome as many of the potential donors as possible and say a few words in support of the project. He certainly looked the part tonight in a well-cut black velvet tuxedo. His dark hair was touched with silver—just enough to give him a classy look. He stood tall and proud as he walked through the crowd, nodding to some and saying a word or two to other attendees.

Julia searched the assembled festival attendees for familiar faces as Drake gently guided her to an older man and woman. He placed his hand at the small of her back as he addressed the wealthy couple. “Julia, I’d like to introduce Mr. And Mrs. George Oglethorpe. They have been long-time supporters of the theatre.”

Julia stepped forward a half-step and extended her hand. “I’m Julia Fairchild. I’m honored to meet you. I love our theatre, too.”

The woman’s face brightened as she recognized the name. “Of course! Dr. Fairchild. Call me Anna. I’ve heard a lot of good things about you.” She took Julia’s hand in both of hers. “You’re so young and pretty for a doctor.”

Julia reddened. She actually felt a little mousey most days, but conceded to herself that she did ‘clean up’ nicely for such events. “Thank you. I was blessed with good genes. How long have you and your husband lived in Parkview?”

“My goodness. Forever. Right out of college anyway. George heard about the paper mill here looking for mechanical engineers and applied right away.” She smiled proudly at him. “We love the town and were never inclined to leave once we settled in. Isn’t that right, dear?” Her husband nodded between sips of his drink. “Are you from here?”

“Not from Parkview. I grew up down the highway on a small farm. My grandma persuaded me to come home and here I am.” Julia felt her eyes well up as she recalled warm memories of time spent with her grandparents. “Thank you for your support of our lovely theatre. The restoration committee will be sharing the plans for the renovation during the program.”

Julia felt Drake’s arm around her waist as he interceded. “Thank you for coming this evening. Please excuse us. I see someone who is clamoring to talk with Dr. Fairchild before the dinner starts.”

Drake took Julia’s arm and as they turned around, they found Gregory Lantz and his wife Sandy who had been standing right behind them. “Greg! So good to see you here tonight. Thanks for coming.” They exchanged nods and handshakes. “Julia is standing in for Karen tonight. She’s also supporting the project.” Julia smiled and nodded. Aside from the perfunctory smiles, Julia sensed a tension between the men, and she moved a step away from Drake to better observe them both.

Greg stirred his gin and tonic vigorously. “I’ve talked with some of the members of the board at the bank, but I don’t have a definite commitment yet for a donation. I think we can come through for $50,000. But nothing close to the million dollars that everyone seems to think the bank can donate.”

“Greg, any amount would be great. I understand it’s been a little tough with the new bank still getting started.” Drake Ashford was the president of the older, long-established Parkview National Bank. He was aware that despite heavy advertising and promotions, the new River City Community Bank was not yet meeting expectations. He was also acutely sensitive to the loss of some of his own banking clients to the new bank, where Greg was Vice President.

Greg bristled. “Actually, we’re meeting our numbers and seeing new business every day. I would think you would have noticed already.” He smirked.

“We’ve noticed a little change, but we’re prepared to handle it.” Drake took a large swallow of his scotch. “Please excuse us. I have some other people to greet. Talk to you later, Greg.” Drake and Julia moved away.

“That man really annoys me,” Drake said under his breath. “He’s so naive. He doesn’t see how Jay is using him. He’s just a ‘yes’ man. But I guess it makes him feel important.”

“What do you mean?” Julia asked, nodding and smiling at some of the faces she recognized. She knew he referred to Jay Morrison, recently divorced and head of the new bank. She felt Drake’s hand shaking as he maneuvered her through the crowd.

“I’ll tell you later. Too many ears here.” He surveyed the guests nearby. “Let’s see…there’s Warren Pontell and his lovely wife Sarah. He’s talked about making a major contribution. His wife was a theatre actress in her younger days. And they have money to burn.” He turned to Julia and wiggled his eyebrows, à la Groucho Marx.

Drake and Julia chatted with the Pontells for a few minutes, using the time to emphasize the benefits of the smaller venue of the “little theatre.” It was designed to be an intimate stage setting with seating for about one hundred fifty people. Until recently, the area had been used for storage and was marginally functional for stage events in its current state.

Julia had found herself daydreaming but tuned back in when she heard Mr. Pontell say, “We’d like to donate $50,000 for the little theatre. Perhaps you can find a way to let us have something to say about naming it.” He grinned broadly as his wife beamed.

“Warren, that’s wonderful!” said Drake. “I’ll talk with the board of directors about naming opportunities. Let me get back to you on details for your donation. Thank you.”

Now grinning, Drake gently guided Julia toward Adam Johns, an influential man in the local union hierarchy, and his wife. He had started working at ESCO Paper Company right out of high school and had worked his way up from the labor pool to an electrician apprenticeship and then to a journeyman electrician. His constituents considered him to be fair and honest. He had an unofficial status in the union as a leader, although he didn’t have an elected or paid position as such.

Adam tugged at the neck of his dress shirt and pulled at the bottom of his dark blue waistcoat. The jacket gaped over his generous girth. He looked uncomfortable in his tuxedo. Julia was sure her mother would have said something like “putting perfume on a goat,” but most likely his wife had insisted he dress up for this occasion. He certainly looked impressive at his height of six foot three inches.

“Mr. and Mrs. Johns, good evening,” said Drake as he offered his hand. “Do you know Dr. Julia Fairchild? She’s helping to support the Theatre Restoration project as we all are.”

“We sure do,” said Adam, returning the handshake. “Dr. Fairchild, you took care of my mom several years back. She was real sick but you got her well and she’s fine now. Thanks to you. In fact, she’s going on a cruise through the Panama Canal with her church group this coming week. She’s always wanted to go on that trip.”

“You’re welcome, Mr. Johns. I do remember your mom—Violette, I believe? She’s a lovely lady with a lot of spunk.” Julia shook his hand before turning to his wife. “Pleased to meet you, Mrs. Johns.”

Mr. Johns turned back to Drake. “Mr. Ashford, some of the guys at the mill want to know if you had talked with our union officials yet about the stock trading going on with our pension funds. And if you know anything, they hope you can tell them. And call me Adam. My wife is Linda.”

“Yes, Adam. I talked with a Scott Sowders in Portland. He’s looking into whether those trading fees can be traced back to any individuals. May I call you when I know something more?”

“Sure. You can call me at ESCO. The operator knows how to reach me. Thanks a lot, Mr. Ashford.”

“You can call me Drake, please. I’ll call you soon and we’ll go from there. Thanks again for being here tonight.”

“Hey. It’s an alright party. My wife is always trying to get me to gussy up. It’s more fun than I thought it would be.” He grinned and saluted with his cocktail.

Julia saw the auctioneer heading their way and alerted Drake. “I’ll check my lipstick while you talk with him. Where are we sitting?”

“Main table,” he said, pointing to the center of the long side of the room. He scowled. “Unfortunately, it appears we’re seated next to Jay Morrison, of all people.”

***

Excerpt from One Will Too Many by PJ Peterson. Copyright 2022 by PJ Peterson. Reproduced with permission from PJ Peterson. All rights reserved.

Author Bio:

PJ is a retired internist who enjoyed the diagnostic part of practicing medicine as well as creating long-lasting relationships with her patients. As a child she wanted to be a doctor so she could “help people.” She now volunteers at the local Free Medical Clinic to satisfy that need to help. She loved to read from a young age and read all the Trixie Belden and Nancy Drew books she could find. It wasn’t until she was an adult that she wrote anything longer than short stories for English classes and term papers in others. Writing mysteries only makes sense given her early exposure to that genre. Sprinkling in a little medical mystique makes it all the more fun.

Catch Up With PJ Peterson:

www.PJPetersonAuthor.com

Goodreads

BookBub – @mizdrpj1

Facebook – PJ Peterson

Tour Participants:

Visit these other great hosts on this tour for more great reviews, interviews, guest posts, and giveaways!

Join In & Win:

This is a giveaway hosted by Partners in Crime Tours for PJ Peterson. See the widget for entry terms and conditions. Void where prohibited.

Get More Great Reads at Partners In Crime Tours

A Dress to Die For

March 6th, 2022When Felicity Philips visits a wedding dress boutique only to find the designer strangled with one of her own veils, she finds herself unwittingly embroiled in yet another desperate investigation.

What could possibly be the motive behind the crime?

A single wedding dress is missing. A one-off design encrusted with jewels, it has been sold to three different brides, all of whom claim the deposit they paid makes it theirs. But who has it?

Find the dress and you find the killer.

Two of the brides are hers – she sent them to the designer!

With arch-rival, Primrose Green, stirring things up and the palace decision on who will run the next royal wedding looming, Felicity employs local P.I. Vince Slater to help solve the case, that’s if he can keep his mind on the job and stop trying to romance her knickers off.

Can she uncover who wanted the dress badly enough to kill for it? She had better pray she does, because this is a dress to die for, and the killing might not be finished yet.

Marriage? It can be absolute murder.

ISLAND BREEZES

She’s no Patricia Fisher, but I think she might want to be. Felicity Philips is a wedding planner whose plans keep going awry.

Three women who have engaged her services want a one of a kind wedding dress. Unfortunately, they all want the same one. Enough to kill for it?

Women keep dying and not only is Felicity’s life threatened, she is losing business. If bad reviews and gossip keep running rampant she won’t have a shot of being the wedding planner for royalty.

Thank you, Mr. Higgs, for another book about Felicity and those pets who communicate with her and sometimes throw a wrench in the works.

***A special thank you to the author who provided a copy without charge.***

When Steve Higgs wrote his debut novel, Paranormal Nonsense, he was a Captain in the British Army. He would love to pretend that he had one of those careers that has to be redacted and in general denied by the government and that he has had to change his name and continually move about because he is still on the watch list in several countries. In truth though, he started out as a mechanic. Not like Jason Statham in the film by that name, sneaking about as a contract killer, more like one of those greasy gits that charge you a fortune and keep your car for a week when all you went in for was a squeaky door hinge.

At school, he was mostly disinterested in every subject except creative writing, for which, at age ten, he won his first award. However, calling it his first award suggests that there have been more, which there have not. Accolades may come but, in the meantime, he is having a ball writing mystery stories, urban fantasies, and crime thrillers and claims to have more than a hundred books forming an unruly queue in his head as they clamor to get out.

Now retired from the military, he lives in the south-east corner of England with a trio of lazy sausage dogs. Surrounded by rolling hills, brooding castles and vineyards, he doubts he will ever leave, the beer is just too good.

Living or Dying

March 5th, 2022Murder at the CDC

March 1st, 2022Murder at the CDC

by Jon Land

February 14 – March 11, 2022 Virtual Book Tour

Synopsis:

2017: A military transport on a secret run to dispose of its deadly contents vanishes without a trace.

The present: A mass shooting on the steps of the Capitol nearly claims the life of Robert Brixton’s grandson.

No stranger to high-stakes investigations, Brixton embarks on a trail to uncover the motive behind the shooting. On the way he finds himself probing the attempted murder of the daughter his best friend, who works at the Washington offices of the CDC. The connection between the mass shooting and Alexandra’s poisoning lies in that long-lost military transport that has been recovered by forces determined to change America forever. Those forces are led by radical separatist leader Deacon Frank Wilhyte, whose goal is nothing short of bringing on a second Civil War. Brixton joins forces with Kelly Lofton, a former Baltimore homicide detective. She has her own reasons for wanting to find the truth behind the shooting on the Capitol steps, and is the only person with the direct knowledge Brixton needs. But chasing the truth places them in the cross-hairs of both Wilhyte’s legions and his Washington enablers.

“A wonderful mystery novel, riveting until the last page.”

–Strand Magazine

“A terrific tale that never lets up.”

–Sandra Brown

Book Details:

Genre: Political Thriller

Published by: Forge

Publication Date: February 15, 2022

Number of Pages: 304

ISBN: 978-1250238894

Series: Margaret Truman’s Capital Crimes, #32 | Each is a stand alone work.

Purchase Links: Amazon | Barnes & Noble | Goodreads

ISLAND BREEZES

You won’t want to put this book down. Tell everyone in your home that they’re on their own because you don’t have time to eat or sleep.

There’s more than one mystery in this book. There’s also more than one law enforcement officer going out on their own to catch the bad guys. They just don’t know exactly how many bad guys that are out there.

I’m not going to tell you any more because I’m afraid I might give away the plot. All I’m going to say is Robert Brixton and Kelly Lofton make a good team.

Thank you, Jon Land, for continuing the series and giving us this book. I’m hoping you’ll give us another one soon.

***A special thank you to PICT for providing this book without charge.***

Read an excerpt:

PROLOGUE

December, 2016

The tanker lumbered through the night, headlights cutting a thin swath out of the storm raging around it.

“I can’t raise them, sir,” said Corporal Larry Kleinhurst, walkie-talkie still pressed tight against his ear.

“Try again,” Captain Frank Hall said from the wheel.

“Red Dog Two, this is Red Dog One, do you read me? Repeat, do you read me?”

No voice greeted him in response.

Kleinhurst pressed the walkie-talkie tighter. “Red Dog Three, this is Red Dog One, do you read me? Repeat, do you read me?”

Nothing again.

Kleinhurst lowered the walkie-talkie, as if to inspect it. “What’s the range on these things?”

“Couple miles, maybe a little less in this slop.”

“How’d we lose both our lead and follow teams?”

Hall remained silent in the driver’s seat, squeezing the steering wheel tighter. Procedure dictated that they rotate the driving duties in two-hour shifts, this one being the last before they reached their destination.

“We must be off the route, must have followed the wrong turn-off,” Kleinhurst said, squinting into the black void around them.

Hall snapped a look the corporal’s way. “Or the security teams did,” he said defensively.

“Both of them?” And when Hall failed to respond, he continued, “Unless somebody took them out.”

“Give it a rest, Corporal.”

“We could be headed straight for an ambush.”

“Or I fucked up and took the wrong turn-off. That’s what you’re saying.”

“I’m saying we could be lost, sir,” Kleinhurst told him, leaving it there.

He strained to see through the big truck’s windshield. They had left the Tooele Army Depot in Tooele County, Utah right on schedule at four o’clock pm for the twelve-hour journey to Umatilla, Oregon which housed the Umatilla Chemical Depot, destination of whatever they were hauling in the tanker. The actual final resting place of those contents, Kleinhurst knew, was actually the Umatilla Chemical Agent Disposal Facility located on the depot’s grounds, about which rumors ran rampant. He’d never spoken to anyone who’d actually seen its inner workings, but the tales of what had already been disposed of there was enough to make his skin crawl, weapons that could wipe out the world’s population several times over.

Which told Kleinhurst all he needed to know about whatever it was they were hauling, now without any security escort.

“We’re following the map, Corporal,” Hall said from behind the wheel, as if needing to explain himself further, a nervous edge creeping into his voice.

He kept playing with the lights in search of a beam level that could better reveal what lay ahead. But the storm gave little back, continuing to intensify the further they drew into the night. Mapping out a route the old-fashioned way might have been primitive by today’s standards, but procedure dictated they avoid the likes of Waze and Google Maps out of fear anything web-based could be hacked to the point where they might be rerouted to where potential hijackers were lying in wait.

Another thump atop the ragged, unpaved road shook Hall and Kleinhurst in their seats. They had barely settled back down when a heftier jolt jarred the rig mightily to the left. Hall managed to right it with a hard twist of the wheel that squeezed the blood from his hands.

“Captain . . .”

“This is the route they gave us, Corporal.”

Kleinhurst laid the map between them. “Not if I’m reading this right. With all due respect, sir, I believe we should turn back.”

Hall cast him a condescending stare. “This your first Red Dog run, son?”

“Yes, sir, it is.”

“When you’re hauling a shipment like what we got, you don’t turn back, no matter what. When they call us, it’s because they never want to see whatever we’re carrying again.”

With good reason, Kleinhurst thought. Among the initial chemicals stored at Umatilla, and the first to be destroyed at the chemical agent disposal facility housed there, were containers of GB and VX nerve agents, along with HD blister agent. The Tooele Army Depot, where their drive had originated, meanwhile, served as a storage site for war reserve and training munitions, supposedly devoted to conventional ordnance. In point of fact, the military also stored nonconventional munitions there in secret, a kind of way station for chemical weapons deemed too dangerous to store anywhere else.

The normal route from Tooele to Umatilla would have taken just over ten hours via I-84 west. But a Red Dog run required a different route entirely off the main roads in order to avoid population centers. The point was to steer clear of anywhere people resided to avoid the kind of attention an accident or spill would have otherwise caused, necessitating a much more winding route Hall and Kleinhurst hadn’t been given until moments prior to their departure. A helicopter had accompanied them through the first stages of the drive, chased away when a mountain storm the forecasts had made no mention of whipped up out of nowhere and caught the convoy in its grasp. Now two-thirds of that convoy had dropped off the map, leaving the tanker alone, unsecured, and exposed, deadly contents and all.

Kleinhurst’s mouth was so dry, he could barely swallow. “What exactly are we carrying, sir?”

Hall smirked. “If I knew the answer to that, I wouldn’t be driving this rig.”

Kleinhurst’s eyes darted to the radio. “What about calling in?”

“We’re past the point of no return. That means radio silence, soldier. They don’t hear a peep from us until we get where we’re going.”

Kleinhurst watched the rig’s wipers slap at the pelting rain collecting on the windshield, only to have a fresh layer form the instant they had completed their sweep. “Even in an emergency? Even if we lost our escorts miles back in this slop?”

“Let me give it to you straight,” Hall snapped, a sharper edge entering his voice. “The stuff we’re hauling in this tanker doesn’t exist. That means we don’t exist. That means we talk to nobody. Got it?”

“Yes, sir,” Kleinhurst sighed.

“Good,” said Hall. “We get where we’re supposed to go and figure things out from there. But right now . . .” His voice drifted, as he stole a glance at the map.

Suddenly Kleinhurst lurched forward, straining the bonds of his shoulder harness to peer through the windshield. “Jesus Christ, up there straight ahead!”

“What?”

“Look!”

“At what?”

“Can’t you see it?”

“I can’t see shit through this muck, Corporal.”

“Slow down.”

Hall stubbornly held to his speed.

“Slow down, for God’s sake. Can’t you see it?”

“I can’t see a thing!”

“That’s it, like the world before us is gone. You need to stop!”

Hall hit the brakes and the rig’s tires locked up, sending the tanker into a vicious skid across the road. He tried to work the steering wheel, but it fought him every inch of the way, turning the skid into a spin through an empty wave of darkness.

“There!” Kleinhurst screamed.

“What in God’s name,” Hall rasped, still fighting to steer when a mouth opened out of the storm like a vast maw.

He desperately worked the brake and the clutch, trying to regain control. He’d been out in hurricanes, tornados, even earthquakes. None of those, though, compared to the sense of airlessness both he and Kleinhurst felt around them, almost as if they were floating over a massive vacuum that was sucking them downward. He’d done his share of parachute jumps for his airborne training and the sensation was eerily akin to those first few moments in freefall before the chute deployed. He remembered the sense of not so much being unable to breathe, as being trapped between breaths for an absurdly long moment.

The rig’s nose pitched downward, everything in the cab sent rattling. The dashboard lights flickered and died, the world beyond lost to darkness as the tanker dropped into oblivion.

And then there was nothing.

CHAPTER 1

“The hand of God is upon You! He is my shepherd and I shall not want!”

Those were the last words high school sophomore Ben McDonald heard before the shooting started. He and the other students clustered around him from the Gilman School in Maryland were on a school field trip to the Capitol Building from their Baltimore prep school, the first such trip taken since academic life returned to a degree of normalcy following the endless coronavirus nightmare. Everyone had shown up in their school uniforms, the buses had left on schedule, and the students felt like pioneers, explorers blazing a trail back into the world beyond shutdowns and social distancing.

The reduction in Capitol tour group size was still in force and had necessitated the two bus-loads of students to be divided into five groups of fifteen, give or take, three chaperones allotted to each. Ben and his twin brother Robbie’s group had gone first and they had found themselves lingering on the Capitol steps, taking pictures and chatting away with their local congressman and senator who’d come out to greet and mingle with the students on the steps at the building’s east front.

“Why are you still wearing a mask?” one of them had asked the congressman, but Ben had already forgotten the answer.

He remembered checking the time on his phone just before he heard the first shots. Ben thought they were firecrackers at first, realizing the truth a breath later when the screams began and bodies started flying.

“I am doing the Lord’s work! I am a sacrifice to his word!”

Somehow Ben gleaned those words through the screams and incessant hail of fire. The shots were coming so fast he wasn’t sure if the shooter was firing on semi or full auto. The boy never actually saw him as more than a shape amid the blur before him, enveloping his vision like a dull haze. The thin sheer curtain drawn over his eyes didn’t keep him from recording bodies crumpling, keeling over, tumbling down the steps. The force of a bullet’s momentum slammed a classmate into him, sparing Ben the ensuing fusillade that turned the other boy’s back into a pin cushion.

My brother!

The panic and shock of those initial seconds had stolen thought of Robbie from him. He wheeled about, covered in the blood of boy who had dropped off the scene.

“Robbie!”

Did he cry out his name or only think it? The steps around him looked blanketed in khaki and blue, pants and blazers that made up his Gilman uniform. The sound of gunfire continued to resound in his ears, but he wasn’t sure the shooter was still firing because no more bodies seemed to be falling. People were running in all directions, crying and screaming, Ben remaining frozen out of fear for his brother.

“Robbie!”

He saw his brother’s sandy blond hair draped down from one of the marble steps onto another. Nothing else at first, just the hair. Maybe he had dove atop a friend who’d been wounded to spare that kid more fire—that was Robbie. But there was no one beneath Him, and . . . And . . .

He wasn’t moving, his arms stretched to the sides on angles that looked all wrong. Ben dropped to his knees next to Robbie, his pants sinking into pooling patches of blood which merged and thickened beneath him. He felt something pinching him along right side of his ribcage and saw his blue shirt darkening with a spreading wave of red in the last moment before he collapsed next to his brother.

***

Excerpt from MURDER AT THE CDC by Jon Land. Copyright 2022 by Jon Land. Reproduced with permission from Jon Land. All rights reserved.

Author Bio:

JON LAND is the USA Today bestselling author of fifty-eight books, including eleven in the critically acclaimed Texas Ranger Caitlin Strong series, the most recent of which, Strong from the Heart, won the 2020 American Fiction Award for Best Thriller and the 2020 American Book Fest Award for Best Mystery/Suspense Novel. Additionally, he has teamed up with Heather Graham for a science fiction series that began with THE RISING (winner of the 2017 International Book Award for best Sci-fi Novel) and continues with BLOOD MOON, to be published in November of 2022. He has also written six books in the Murder, She Wrote series of mysteries and has more recently taken over Margaret Truman’s Capital Crimes series, with his second effort, MURDER AT THE CDC, to be published in February of 2022. Jon is known as well for writing the film DIRTY DEEDS, a teen comedy starring Milo Ventimiglia and Zoe Saldana, which was released in 2005. A graduate of Brown University, he received the 2019 Rhode Island Authors Legacy Award for his lifetime of literary achievements.

Catch Up With Our Author:

JonLandBooks.com

Goodreads

BookBub – @JonLand2

Twitter – @JonDLand

Facebook – @JonLandAuthor

Tour Participants:

Visit these other great hosts on this tour for more great reviews, interviews, guest posts, and giveaways!

Join In and Enter to Win:

This is a giveaway hosted by Partners in Crime Tours for Jon Land. See the widget for entry terms and conditions. Void where prohibited.

Get More Great Reads at Partners In Crime Virtual Book Tours

A Man’s Heart

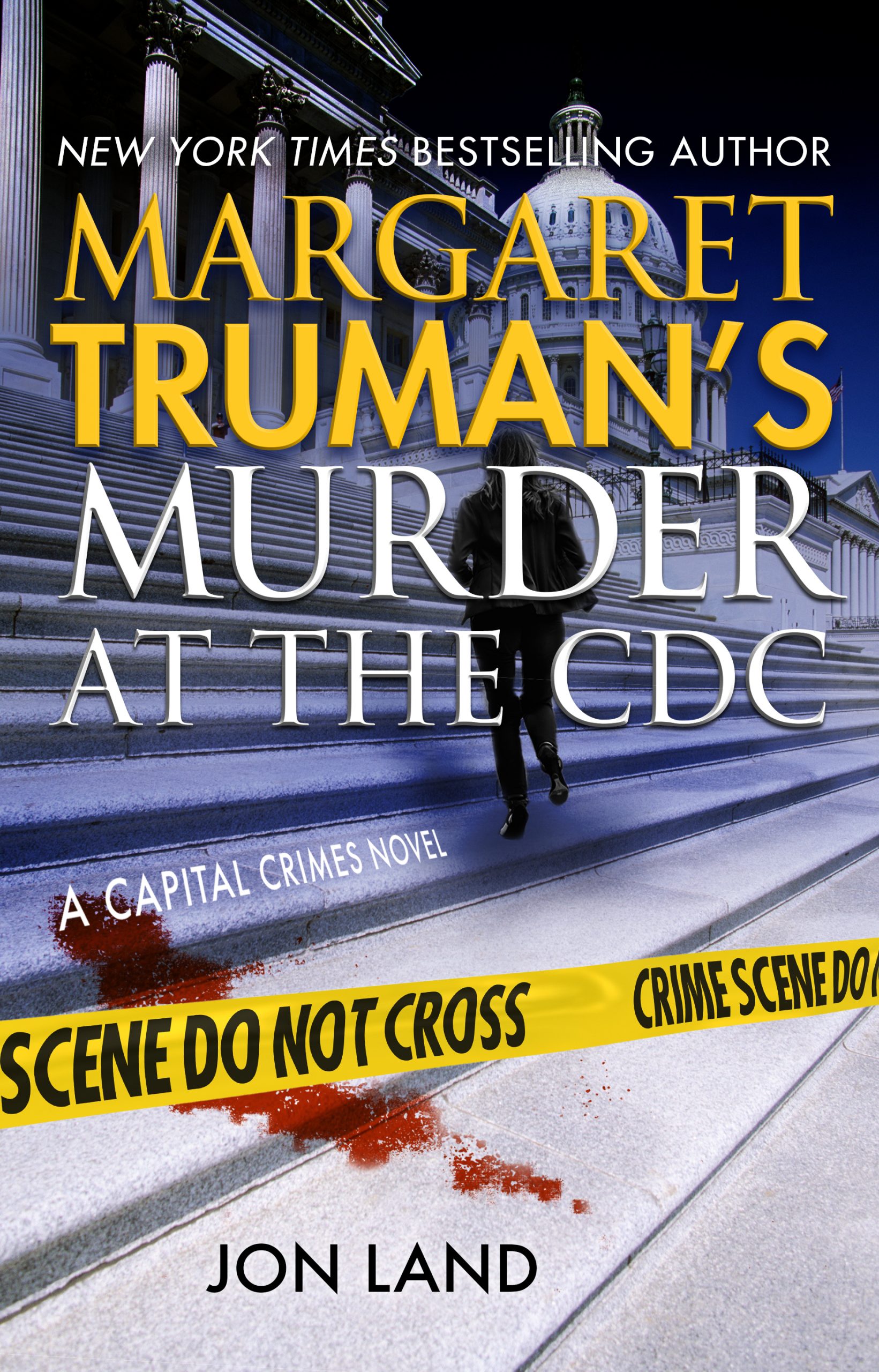

February 26th, 2022I Take My Coffee Black

February 21st, 2022As a six-foot, two-inch, dreadlocked Black man, Tyler Merritt knows what it feels like to be stereotyped as threatening, which can have dangerous consequences. But he also knows that proximity to people who are different from ourselves can be a cure for racism.

Tyler Merritt’s video “Before You Call the Cops” has been viewed millions of times. He’s appeared on Jimmy Kimmel and Sports Illustrated and has been profiled in the New York Times. The viral video’s main point – the more you know someone, the more empathy, understanding, and compassion you have for that person – is the springboard for this book. By sharing his highs and exposing his lows, Tyler welcomes us into his world in order to help bridge the divides that seem to grow wider every day.

In I Take My Coffee Black, Tyler tells hilarious stories from his own life as a Black man in America. He talks about growing up in a multicultural community and realizing that he wasn’t always welcome, how he quit sports for musical theater (that’s where the girls were) to how Jesus barged in uninvited and changed his life forever (it all started with a Triple F.A.T. Goose jacket) to how he ended up at a small Bible college in Santa Cruz because he thought they had a great theater program (they didn’t). Throughout his stories, he also seamlessly weaves in lessons about privilege, the legacy of lynching and sharecropping and why you don’t cross Black mamas. He teaches listeners about the history of encoded racism that still undergirds our society today.

By turns witty, insightful, touching, and laugh-out-loud funny, I Take My Coffee Black paints a portrait of Black manhood in America and enlightens, illuminates, and entertains – ultimately building the kind of empathy that might just be the antidote against the racial injustice in our society.

ISLAND BREEZES

I’m from the old school, I guess. I’ve spent most of my life listening to music from my parents generation. Mostly music from the 40’s, 50’s and 60’s. I also discovered the pleasures of reggae while working on ships.

I did not know (nor even had heard of Tyler Merritt). The man is an inspiration. He’s very honest as to the lifestyle he had versus the man he has become.

I admire him. I would like to sit down and drink a cup of coffee with him.

Thank you, Mr. Merritt, for opening your heart to us.

***Book provided without charge by Canaan of Hachette Book Group.***

Tyler Merritt is an actor, musician, comedian, and activist behind The Tyler Merritt Project. Raised in Las Vegas he has always had a passion for bringing laughter, grace, and love into any community that he is able to be a part of. For over twenty years now he has spoken to audiences ranging from elementary school students to nursing home seniors. His television credits include ABC’s Kevin Probably Saves The World, Netflix’s Messiah, Netflix’s Outer Banks, Disney/Marvel’s Falcon and the Winter Soldier and Apple TV’s upcoming series Swagger. Tyler’s viral videos “Before You Call the Cops”and “Walking While Black” have been viewed by over 60 million people worldwide with “Before You Call The Cops” being voted the number one most powerful video of 2020 by NowThis Politics. He is a Cancer survivor who lives in Nashville, Tennessee