In 1914, the war to end all wars turns the worlds of John Patrick Scott, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, H.G. Wells, Rebecca West and Harry Houdini upside down. Doyle goes back to ancient China in his hunt for that “red book” to help him write his Sherlock Holmes stories. Scott is hell-bent on finding out why his platoon sergeant has it out for him, and they both discover that during the time of Shakespeare every day is a witch-hunt in London. Is the ability to travel through time the ultimate escape from the horrific present, or do ghosts from the past come back to haunt those who dare to spin the Wheel of Karma?

The Time Traveler Professor, Book Two: A POCKETFUL OF LODESTONES, sequel to SILENT MERIDIAN, combines the surrealism of Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five with the supernatural allure of Susanna Clarke’s Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell set during WWI on the Western Front.

This is another good book in The Time Traveler Professor series. I do suggest that you read the previous book prior to reading this one. The author does give a brief synopsis of that book, but you will get a better handle on the characters if you read it yourself.

I enjoyed the many adventures of John and Arthur, but did get tired of the war and all the dead bodies John had to bury, etc.

I look forward to the next book, and hoping we can get to the finish of World War I.

Thank you, Ms Crowens, for your great imagination.

Chapter One: Kitchener’s Call to Arms

August 1914

“Have you ever killed a man before?”

I had, but close to three hundred years ago. So, I lied and just shook my head.

“Your name, son?” the recruitment officer asked.

“John Patrick Scott,” I said, with pride.

The officer handed me a card to fill out. “Write your date of birth, where you live and don’t skip any questions. When finished, bring this over to Line B.”

Born during the reign of Queen Victoria, somehow or other I managed to travel to the 23rd century, feudal Japan, and ancient China long before the Great War started. The army wanted to know all the places I had traveled, but it was doubtful that much information was required.

Since the war to end all wars commenced, recruiting centers sprang up like wildflowers. This one took over an Edinburgh public library. If unaware as to why the enthusiastic furor, one would’ve guessed the government gave away free land tracts with titles.

“Let’s see how clever you blokes are. Tell me the four duties of a soldier,” another enlistment administrator called out.

An overeager Glaswegian shouted, “Obedience, cleanliness, honesty and sobriety, sir!”

The chap next to him elbowed his side. “Takes no brains to read a bloody sign.”

Propaganda posters wallpapered the room with solicitous attempts at boosting morale. Kitchener wanted us and looked straight into our eyes. Proof of our manhood or perhaps stupidity. Queues of enthusiasm wound around the block. Impatient ones jumped the lines. We swore our allegiance to the King over a bible. As long as the war lasted, our lives were no longer our own.

Voices from men I’d never see again called out from the crowd.

“It’ll be over in six weeks.”

“Are you so sure?”

“Check out those men. All from the same cricket team. Play and die together. Medals of Valor in a blink. Local heroes with celebrations.”

“I’ll drink to that.”

A crusty old career soldier yelled out to the volunteers, “Does anyone speak Flemish?”

Suddenly the place got quiet. Then he looked at me. “Soldier, do you know anything besides the King’s English? French?”

“Fluent German,” I said. “That should be helpful.”

“Since when were you with the Bosches?”

“Fourteen years, sir. Before the war.”

“And what were you doing in enemy territory?”

“Worked as a teacher. A music professor and a concert pianist when I could get the engagements and sometimes as an amateur photographer. They weren’t our enemies then, sir.”

“Have you ever shot a rifle, son?”

“Actually, I have…”

“Find a pair of boots that fits you, lad. Hustle now. Time’s a wasting.”

The Allied and German armies were in a Race to the Sea. If the Germans got there first, then England was in danger of invasion. Basic training opened its arms to the common man, and it felt strange to be bedding alongside Leith dockworkers and farmers, many underage, versus the university colleagues from my recent past. Because of the overwhelming need for new recruits, training facilities ran out of room. The army took over church halls, local schools and warehouses in haste. Select recruits were billeted in private homes, but we weren’t so fortunate.

Except for acquired muscles, I slimmed down and resembled the young man that I was in my university days except with a tad more gray hair, cut very short and shaved even closer on the sides. No more rich German pastries from former students as part of my diet. At least keeping a clean-shaven face wasn’t a challenge since I never could grow a beard. Wearing my new uniform took getting used to. Other recruits laughed, as I’d reach to straighten my tie or waistcoat out of habit despite the obvious fact that I was no longer wearing them.

While still in Scotland during basic training, I started to have a series of the most peculiar dreams. My boots had not yet been muddied with the soil of real battlefields. New recruits such as I, had difficult adjustments transitioning from civilian life. Because of my past history of lucid dreaming, trips in time travel and years of psychical experimentation I conducted both on my own and with my enthusiastic and well-studied mentor, Arthur Conan Doyle, my nightmares appeared more real than others. My concerns were that these dreams were either actual excursions into the Secret Library where the circumstances had already occurred or premonitions of developments to come.

The most notable of these episodes occurred toward the end of August in 1914. In this dream, I had joined another British platoon other than my own in Belgium on the Western Front. We were outnumbered at least three to one, and the aggressive Huns surrounded us on three sides.

Whistles blew. “Retreat!” yelled our commanding officer, a privileged Cambridge boy, barely a man and younger than I, who looked like he had never seen the likes of hardship.

We retreated to our trenches to assess what to plan next, but instead of moving toward our destination everyone froze in their tracks. Time was like a strip of film that slowed down, spooled off track, and jammed inside a projector. Then the oddest thing happened to our enemy. For no apparent reason, their bodies jerked and convulsed as if fired upon by invisible bullets over the course of an hour.

When the morning fog lifted, the other Tommies and I broke free from our preternatural standstill and charged over the top of the trenches with new combat instructions. Half of our platoon dropped their rifles in shock. Dead Huns, by the thousands, littered No man’s land long before we had even fired our first retaliatory shot!

I woke up agitated, disoriented and in a cold sweat. Even more disturbing was finding several brass shell casings under my pillow — souvenirs or proof that I had traveled off somewhere and not imagined it. I roused the sleeping guy in the next bed and couldn’t wait to share this incredible story.

“Shush!” he warned me. “You’ll wake the others.”

Meanwhile, he rummaged inside his belongings and pulled out a rumpled and grease-stained newspaper clipping that looked and smelled like it had originally been used to wrap up fish and chips.

He handed it to me with excitement. “My folks sent this me from back home.”

The headlines: “Angels sited at the Battle of Mons”

Almost as notable was the article’s byline written by my best friend from the University of Edinburgh, Wendell Mackenzie, whom I had lost track of since the war started.

He begged me to read on.

“Hundreds of witnesses claimed similarities in their experiences. There were rumors aplenty about ghostly bowmen from the Battle of Agincourt where the Brits fought against the French back in 1415. Inexplicable apparitions appeared out of nowhere and vanquished German enemy troops at the recent Battle of Mons.”

“This looks like a scene from out of a storybook.” I pointed to an artist’s rendition and continued.

“Word spread that arrow wounds were discovered on corpses of the enemy nearby, and it wasn’t a hoax. Others reported seeing a Madonna in the trenches or visions of St. Michael, another saint symbolizing victory.”

“Now, I don’t feel so singled out,” I said and handed the newspaper articles back to my comrade.

For weeks, I feared talking to anyone else about it and insisted my mate keep silent. Even in wartime, I swore that I’d stay in touch with my closest acquaintances, Wendell Mackenzie and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. It was easier to keep abreast of Arthur’s exploits, because of his public celebrity. On the other hand, Wendell, being a journalist, could be anywhere in the world on assignment.

* * *

Dear Mr. and Mrs. Mackenzie,

I regret having missed Wendell when he never made it over to visit Scotland, and you wonder if someone up above watches over us when we make decisions where to go and when. In my case it was when I decided to take a summer vacation and travel to Edinburgh before the war. Those without passports or proper documentation endured countless detours and delays getting back to their respective homelands. One of Mrs. Campbell’s lodgers had been detained in France.

With nothing to return to back in Germany, I joined the Royal Scots. Military training commenced in Edinburgh, and at least they had us wearing uniforms of pants tucked into gaiters as opposed to the Highland troops who wore kilts. Although I was born and bred in Scotland, as a Lowlander that’s one outfit you’d have to force me into with much duress.

Our tasks would be in the Scots Territorial units deployed on our coastline in case of an enemy invasion. Potential threats could come from spies or submarines, but most say that the worst enemy has been the frigid wind blowing off the North Sea.

As there is always talk about combining forces and transfers, my aunt can always forward letters. It would mean more than the world to hear from Wendell saying that not only is he all right, but also in good spirits.

Yours most devoted,

Private John Patrick Scott

* * *

Dear Arthur,

In our last correspondence, I conveyed that I was unable to return to my teaching post in Stuttgart. With your tour in the Boer War as my inspiration, I joined the military. We learned the basics: how to follow commands, first aid, march discipline and training in all matters of physical fitness. My feet have been in a constant state of rebellion, since my previous profession as a pianist was a sedentary occupation.

Deployment was supposed to be along the coast of Scotland, but the army reassigned me despite first promises because of too many staggering losses on the Western Front. I requested to be part of the air corps and a pioneer in new battle technology, but my recruiting officers had other plans. Our regiment left for Ypres in Belgium. None of the Tommies could pronounce the name of this place, so everyone called it Wipers. You’re no stranger to war, but everyone has been surprised that it lasted longer than anticipated.

Yours Most Devoted,

Private John Patrick Scott

* * *

Troops from all over under the wing of the British Expeditionary Forces piled on to ships to sail out to the continent. The locals from Edinburgh didn’t expect to leave bonnie ole Scotland. They told us we’d defend our shores from foreign invasions. I’d crossed the North Sea before, but then it was a sea of hope and a new life full of opportunity when I got my scholarship to continue my musical studies in Germany, now the enemy.

I turned to the nearest stranger, hoping that a random conversation would break the monotonous and never-ending wait until we set anchor in Belgium. “How was your basic training?”

“Three months at an abandoned amusement park,” the soldier replied. “We trained for the longest time in our street clothes and were told they ran out of uniforms. Probably sent recycled ones after the first troops died. Used wooden dummy rifles until the real ones arrived. What about you?”

“We used an abandoned dance hall. Never could get used to waking at 5:30 a.m.”

“Word got around that in Aldershot soldiers had luxury facilities with a billiards room, a library, private baths and a buffet. I suspect that was for the regulars, the old-timers, not new recruits like us.”

“I should’ve enlisted elsewhere,” I grumbled, not that it would’ve made much of a difference if we’d all die in the end.

He pointed to my face and examined my flawless hands. “You don’t look like much of an outdoorsman. Pale, hairless complexion. No scars.”

“I’m a concert pianist.”

“Not much use on the Front.”

“Probably not. Excuse me, I need some air.” I bundled up in my great coat, wrapping my muffler a wee bit tighter.

Wasn’t sure which were worse — the soldiers with their asphyxiating cigarettes or numbing sleet turning into ice pellets. Hadn’t gotten my sea legs, yet. Stormy swells churned my stomach. Sweet Scotland. Lush green grass and the sky the color of blue moonstone. Never thought I’d be so sentimental. Continued staring until brilliant hues of the shoreline merged into dismal grays of a foggy horizon. In the transition from civilian to soldier, I stepped through a door of no return unless I desired to come back home in a coffin.

Chapter Two: The Other Lost World

Ypres, Belgium Late fall, 1914

A sea of strange men, but all comrades-in-arms, all recent transplants marched to their assignments and followed orders without question to who-knows-where on the way to the battlefield sites. We sallied forth, anonymous troops with a distorted sense of time and distance through the streets of has-been cities, once thriving communities. Poetry in ruination.

As we marched through the Grote Markt (Grand Market) heading out toward the Menenpoort (or Menen Gate) I didn’t expect to get an education. The soldier to my left kept talking out loud and compared notes of local tourist attractions. He was probably unaware that anyone else had overheard his comments.

“That long, distinctive building with the church hiding behind it must be the Hallen… or their Cloth Hall. There were impressive paintings on the interior walls of the Pauwels Room depicting the history of this town and its prosperous textile trade.”

“How do you know this?” I asked, trying not to attract too much attention.

“I’m a historian. Used to teach at a priory school in Morpeth.”

Perhaps I was naïve, but I asked, “Why would the armed forces recruit someone with a background in history?”

“That didn’t influence my enlistment although I’m sure it’ll come in handy somewhere. Before the war, I traveled all over Europe when time permitted. I brought original postcards with me as to what this town used to look like. It’s frightening to see the difference.”

“Your name?” I asked.

“Private Watson. What about you?”

“Not John Watson, by any chance?”

“No, Roger Watson, why?”

I shook my head thinking about Arthur and bit my lip to hide a slight smile. “Oh nothing… My name is Private Scott, John Patrick Scott.”

“What brings you to this dismal corner of the earth?”

“Ich war ein Musiklehrer. Pardon me, sometimes I break into German. I’m from Edinburgh but was living in Germany as a music teacher. Can’t be doing that sort of thing now.”

“I suppose not.”

“Roger, sorry to have eavesdropped, but it sounded so interesting. Then you are familiar with the area we just marched through?”

“That was the central merchant and trading hub of Ypres and has been since the mid-fifteenth century. On the north side over there is St. Martin’s Cathedral. You can already see the damage from German attacks.”

There was no escaping the needless destruction by aggressive enemy bombing. We continued marching forward in formation. A little way beyond the city gate, we passed by the remains of a park and children’s playground. The soldiers took a rest break and snacked on portable rations.

Many of them took off their boots and massaged their feet. Not too far away, I found a shattered brick in the rubble of what had been a schoolhouse and brought it back to where everyone was having his makeshift picnic.

Watson noticed that I kept twirling the small fragment in my hand while intermittently closing my eyes. “Scott, what are you doing?”

“Pictures form in my mind similar to movies. It’s the art of psychometry,” I replied.

“Psycho — what?” Another soldier overheard us talking.

“Sounds like something from Sigmund Freud,” one called out.

“Not at all, it’s like a psychical gift or talent. It has nothing to do with psychoanalysis.”

“What’s the point?” the first one asked.

I felt under pressure to put my thoughts into words. “I can understand what building this brick was part of when it was intact and what was here before it was destroyed.”

“That’s incredible!” Watson exclaimed. “If you are able to uncover bygone times by psychical means, I am all ears.”

When everyone else discounted my talent, Watson gave it full praise. Others became impatient and weren’t interested in our sidebar history lesson.

“Can you use those skills beyond inanimate objects?” one soldier asked.

“Find me an object, someone’s former possession,” I said.

Another soldier found a broken pocket watch not far from a trampled garden. He tossed it over, and I caught it with both hands. When I closed my eyes, the images materialized in my mind’s eye.

“A loving grandfather was reading to his grandchildren from an illustrated story book. He was balding. Wore spectacles. Had a trimmed white beard.

“‘Time for bed,’ he said, looking at his watch. Tick tock, tick tock. It was a gift from his father.

“He kissed each grandchild on the forehead as they scampered off. Two girls, one boy, all in their nightgowns. The tallest girl was a redhead with… pink ribbons in her long, curly hair. Then the bombs dropped. Fire. The roof collapsed. All was lost. Then… then… Oh my God!”

“Scotty, what’s wrong?” Watson asked.

I looked at the blank faces around me. “You don’t see him?”

Watson was baffled. “See who?”

“That grandfather,” I said, horrified and clutching onto that timepiece. His ghost was standing right in front of me!

Then I realized that no one else was capable of seeing him. Inside, I panicked until my frozen fingers let go of the watch, and it tumbled into the dirt. That’s when his phantasmal form vanished, but there were still indelible memories impressed upon the ether that refused to fade with the passage of time.

Warning bells tolled from a nearby church. “Quick, run for cover!” our commanding officer shouted.

Double-time over to shelter. Incoming bombs whistled and boomed in the distance. Civilians followed, carrying their most precious possessions, also fleeing for their lives.

The sanctuary already suffered from shell damage that left large gaping holes in its roof. Birds nested above the pulpit. Cherished religious statuary had been knocked over and broken. Several nuns rushed up and motioned the way for us to take refuge in the basement. We joined the crowd of scared families, members of the local community.

“Isn’t Britain giving them haven?” I asked Watson. “I thought most of the civilians evacuated by now.”

“There are still the ones who want to hold out,” he explained. “Wouldn’t you if your entire life and livelihood were here for multiple generations? That’s why they’re counting on us, but the Germans are relentless. Ypres is right on the path of strategic routes to take over France.”

When several farmers brought over their pigs and chickens, our retreat began to resemble a biblical nativity scene. From inside the cellar, we could hear the rumble of the outside walls collapsing.

“We’ll be trapped!” People yelled out in panic.

A group of sisters prayed in the corner. Our trench diggers readied themselves to shovel us out if it came to that. One terror-stricken woman handed me a screaming baby.

“I found him abandoned.” At least that’s what I thought she said in Flemish, but none of us could understand her. Confused and without thinking, I almost spoke in Japanese, but that would’ve been for the wrong place and an entirely different century during a different lifetime.

“What will I do with him?” I said to her in German, but she didn’t comprehend me either. I couldn’t just place him down in a corner. We’d be marching out in a matter of minutes.

I approached a man with his wife and three other children. First I tried English, then German, random words of French, and then I tried Greek and Latin from my school days. Finally I resorted to awkward gestures to see if he’d take the child. But he shook his head, gathered his brood and backed off.

Troops cleared a path out of the cellar. We needed to report to our stations before nightfall.

“Sister, please?” I begged one nun, interrupting her rosary. To my relief, she took the infant.

“Oh Mon Dieu!” I cried out in the little French that I knew. “Danke, thank you, merci boucoup.” Then I ran off to join the others.

Watson slapped me on the back. “Looked like you were going to be a father, mate.”

“Not yet. Got a war to fight,” I replied.

***

Excerpt from The Time Traveler Professor, Book Two: A Pocketful of Lodestones by Elizabeth Crowens. Copyright © 2019 by Elizabeth Crowens. Reproduced with permission from Elizabeth Crowens. All rights reserved.

Crowens has worked in the film and television for over twenty years and as a journalist and a photographer. She’s a regular contributor of author interviews to an award-winning online speculative fiction magazine, Black Gate. Short stories of hers have been published in the Bram Stoker Awards nominated anthology, A New York State of Fright and Hell’s Heart. She’s a member of Mystery Writers of America, The Horror Writers Association, the Authors Guild, Broad Universe, Sisters in Crime and a member of several Sherlockian societies. She is also writing a Hollywood suspense series.

Visit these other great hosts on this tour for more great reviews, interviews, guest posts, and giveaways!

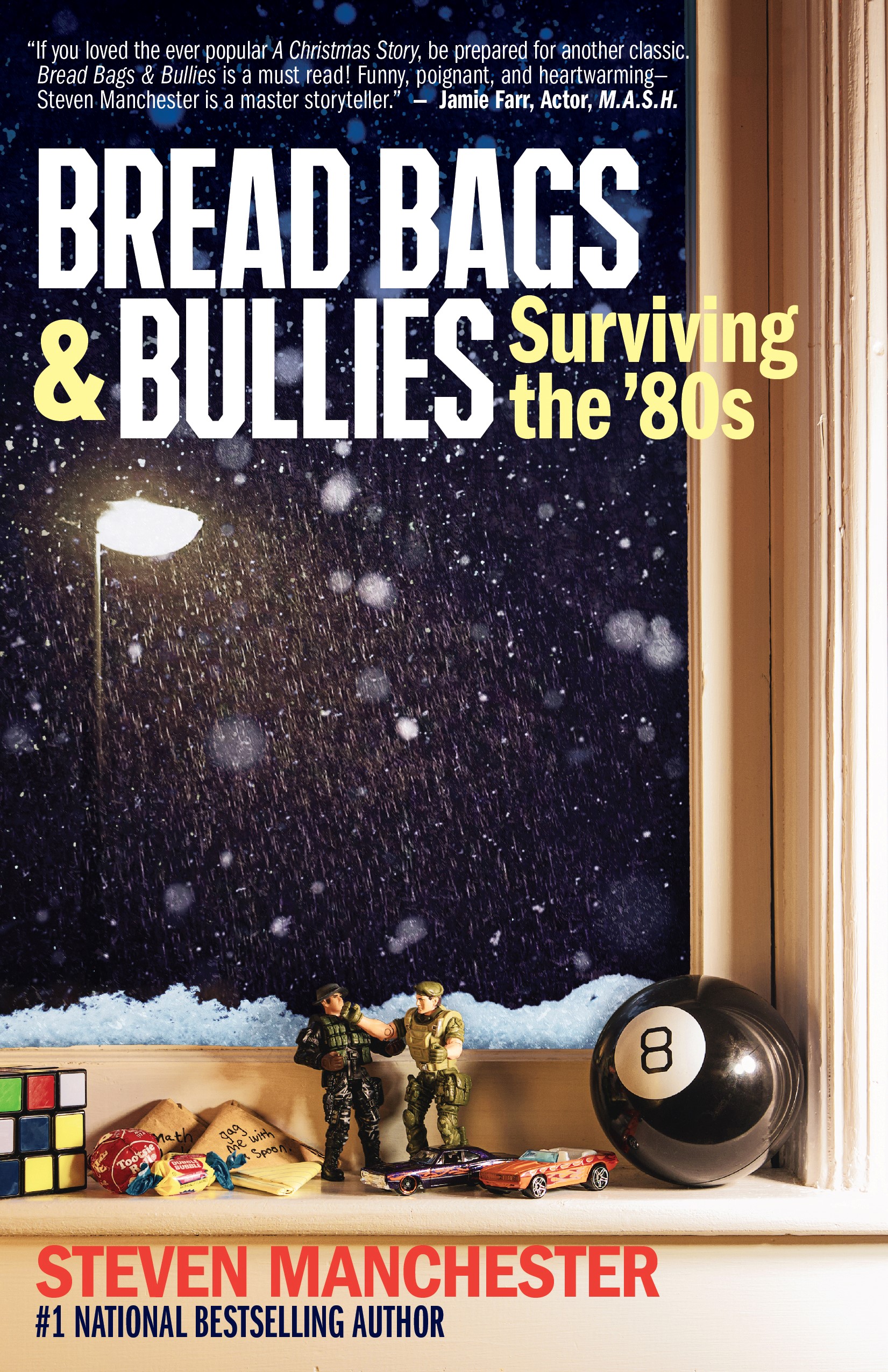

It’s the winter of 1984. Twelve-year-old Herbie and his two brothers—Wally and Cockroach—are enjoying the mayhem of winter break when a late Nor’easter blows through New England, trapping their quirky family in the house. The power goes out and playing Space Invaders to AC DC’s Back in Black album is suddenly silenced—forcing them to use their twisted imaginations in beating back the boredom. At a time when the brothers must overcome one fear after the next, they learn that courage is the one character trait that guarantees all others.

It’s the winter of 1984. Twelve-year-old Herbie and his two brothers—Wally and Cockroach—are enjoying the mayhem of winter break when a late Nor’easter blows through New England, trapping their quirky family in the house. The power goes out and playing Space Invaders to AC DC’s Back in Black album is suddenly silenced—forcing them to use their twisted imaginations in beating back the boredom. At a time when the brothers must overcome one fear after the next, they learn that courage is the one character trait that guarantees all others.

Steven Manchester is the author of the #1 bestsellers Twelve Months, The Rockin’ Chair, Pressed Pennies and Gooseberry Island; the national bestsellers, Ashes, The Changing Season and Three Shoeboxes; and the multi-award winning novels, Goodnight Brian and The Thursday Night Club. His work has appeared on NBC’s Today Show, CBS’s The Early Show, CNN’s American Morning and BET’s Nightly News. Three of Steven’s short stories were selected “101 Best” for Chicken Soup for the Soul series. He is a multi-produced playwright, as well as the winner of the 2017 Los Angeles Book Festival and the 2018 New York Book Festival. When not spending time with his beautiful wife, Paula, or their four children, this Massachusetts author is promoting his works or writing.

Steven Manchester is the author of the #1 bestsellers Twelve Months, The Rockin’ Chair, Pressed Pennies and Gooseberry Island; the national bestsellers, Ashes, The Changing Season and Three Shoeboxes; and the multi-award winning novels, Goodnight Brian and The Thursday Night Club. His work has appeared on NBC’s Today Show, CBS’s The Early Show, CNN’s American Morning and BET’s Nightly News. Three of Steven’s short stories were selected “101 Best” for Chicken Soup for the Soul series. He is a multi-produced playwright, as well as the winner of the 2017 Los Angeles Book Festival and the 2018 New York Book Festival. When not spending time with his beautiful wife, Paula, or their four children, this Massachusetts author is promoting his works or writing.

Lou Aronica is the author of the USA Today bestseller The Forever Year and the national bestseller Blue. He also collaborated on the New York Times nonfiction bestsellers The Element and Finding Your Element (with Ken Robinson) and the national bestsellers The Culture Code (with Clotaire Rapaille) and The Greatest You (with Trent Shelton). Aronica is a long- term book publishing veteran. He is President and Publisher of the independent publishing house The Story Plant.

Lou Aronica is the author of the USA Today bestseller The Forever Year and the national bestseller Blue. He also collaborated on the New York Times nonfiction bestsellers The Element and Finding Your Element (with Ken Robinson) and the national bestsellers The Culture Code (with Clotaire Rapaille) and The Greatest You (with Trent Shelton). Aronica is a long- term book publishing veteran. He is President and Publisher of the independent publishing house The Story Plant.